Brownfield is best

How we put brownfield land on the map

One of the reasons CPRE exists is to protect the countryside – to make sure that, alongside our mission to promote the joys and benefits of our green land and make it even better, we find ways to stop its unnecessary destruction.

In recent years, the need for housing has created a pressure on what’s known as greenfield land – areas that haven’t been developed previously.

We have some major quibbles on what’s built and for whom if we’re going to tackle the crisis in housing affordability - but what we’ve known for a long time is that there is lots of land that has been built on previously that we can recycle for building housing. This is often called brownfield land.

Previously on brownfield...

Using brownfield for housing emerged onto the political agenda when the new Labour government set a national target in 1998 to make sure 60% of all new development was built on brownfield land. This was reiterated in a report written by the Urban Task Force, chaired by Richard Rogers, and including CPRE’s Tony Burton in its membership. The report concluded that brownfield sites in urban areas should be redeveloped for different types of housing at medium and high density, like the award-winning social housing development at Goldsmith Street in Norwich.

This focus on brownfield development led to the proportion of new housing development on brownfield land reaching a high of 81% in 2008.

But the target was removed in 2010 as part of the changes that ultimately became the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). The new coalition government felt it hindered the development of new homes, as well as their quality. The government also abandoned the requirement for councils to log brownfield land suitable for development.

In just three years, between the high of 2008 and 2011, the proportion of new housing on brownfield sites fell from 81% to 68%.

By 2015-16, just 61% of new addresses were created on brownfield land.

CPRE disagreed with the government’s changes – we didn’t think brownfield use was related to design quality – and we felt some developers’ preference for building on green fields wasn’t a good excuse to abandon a commitment to brownfield use and start tearing up more of our countryside. We published a paper on Removing obstacles to brownfield development to give them ideas on how brownfield building could get moving.

And we called on the government to put brownfield first again.

How much brownfield?

But now there was a problem. Without councils recording suitable brownfield land, nobody knew how much was available. It provided a perfect excuse for developers to say there wasn’t land available. To put ‘brownfield first’, councils needed to know what brownfield land they had that was suitable for housing.

So, in 2014, CPRE decided to find out.

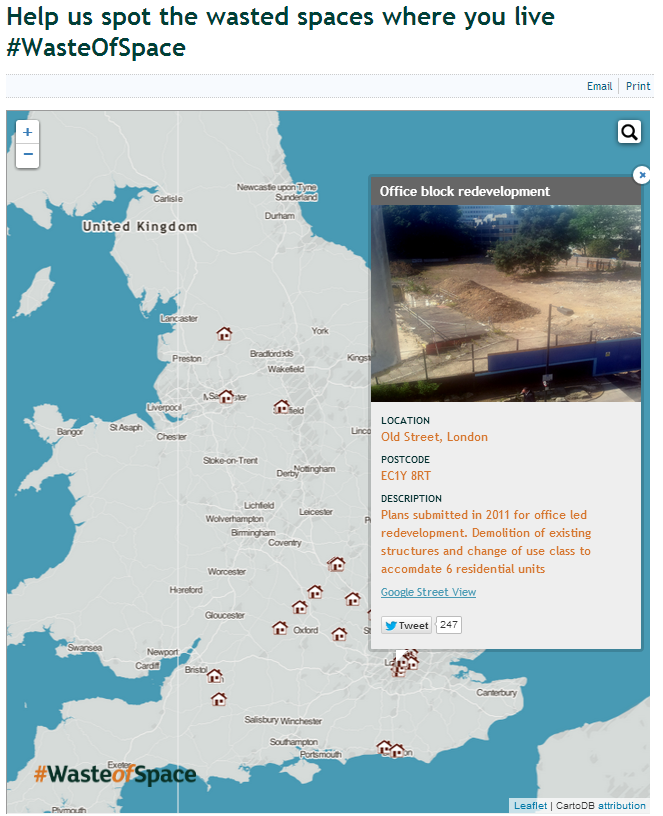

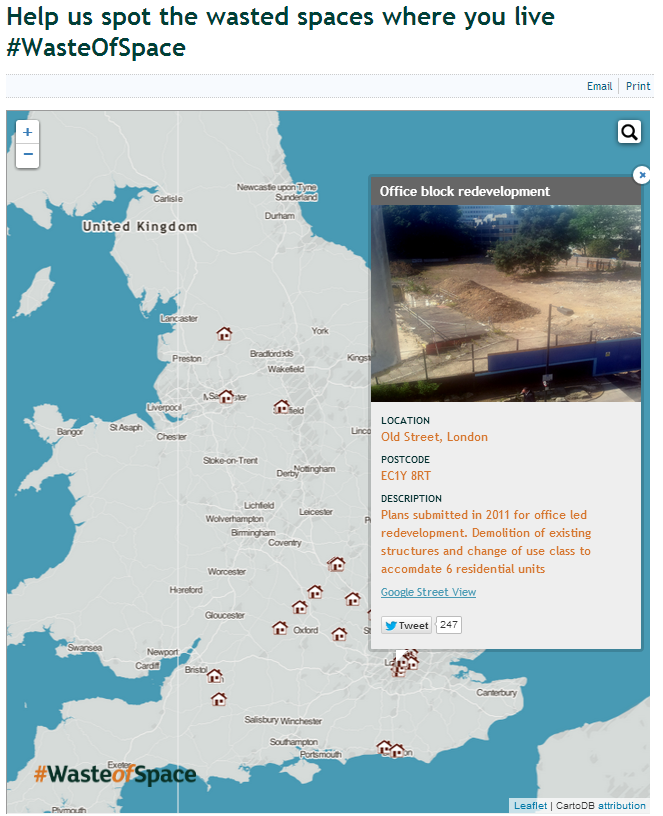

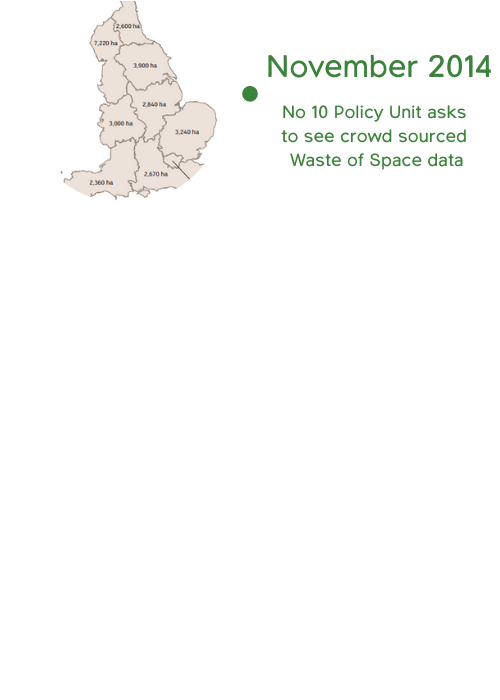

Our Waste of Space campaign had a two-pronged approach. We used our social media channels to crowd-source brownfield sites that could be used for housing. At the same time, we commissioned researchers from the University of the West of England to analyse all the most recent data on brownfield and extrapolate that to give a national picture.

Four hundred of our supporters responded to our call for details and photos of suitable brownfield land for housing. The region with the highest number of submissions was the south east (119 sites, not including 35 in London), followed by the West Midlands (73) and the south west (66). Most popular sorts of sites nominated included derelict sites (148) and former factories/industrial sites (56).

The researchers’ results were even more spectacular. Their extrapolation from the data they uncovered suggested that England had enough brownfield land for at least 976,000 homes.

They also suggested that brownfield is not a finite resource. In other words, more brownfield land tends to become available as other brownfield is used – it's recyclable.

The government told us our estimate was ‘wildly optimistic’.

Head of Land Use and Planning Paul Miner on how CPRE's brownfield campaigning made a difference

Head of Land Use and Planning Paul Miner on how CPRE's brownfield campaigning made a difference

But now there was a problem. Without councils recording suitable brownfield land, nobody knew how much was available. It provided a perfect excuse for developers to say there wasn’t land available. To put ‘brownfield first’, councils needed to know what brownfield land they had that was suitable for housing.

So, in 2014, CPRE decided to find out.

Our Waste of Space campaign had a two-pronged approach. We used our social media channels to crowd-source brownfield sites that could be used for housing. At the same time, we commissioned researchers from the University of the West of England to analyse all the most recent data on brownfield and extrapolate that to give a national picture.

Four hundred of our supporters responded to our call for details and photos of suitable brownfield land for housing. The region with the highest number of submissions was the south east (119 sites, not including 35 in London), followed by the West Midlands (73) and the south west (66). Most popular sorts of sites nominated included derelict sites (148) and former factories/industrial sites (56).

The researchers’ results were even more spectacular. Their extrapolation from the data they uncovered suggested that England had enough brownfield land for at least 976,000 homes.

They also suggested that brownfield is not a finite resource. In other words, more brownfield land tends to become available as other brownfield is used – it's recyclable.

The government told us our estimate was ‘wildly optimistic’.

Head of Land Use and Planning Paul Miner on how CPRE's brownfield campaigning made a difference

Head of Land Use and Planning Paul Miner on how CPRE's brownfield campaigning made a difference

Building on brownfield evidence

With the new evidence, we set about lobbying ministers, MPs and explaining our work to civil servants. They started showing an interest: the No 10 Policy Unit asked to see what sites were on our crowd-sourced list.

In March the following year we published the policy paper Better brownfield suggesting that large scale brownfield sites require a comprehensive approach to development - and European experience could show us the way. It also looked at small-scale brownfield sites in England, finding that a register of these sites together with a flexible approach to space standards could make the most of their potential.

A commitment to brownfield land appeared in Conservative and Liberal Democrat manifestos for the 2015 elections.

'We will require local authorities to have a register of what is available, and ensure that 90 per cent of suitable brownfield sites have planning permission for housing by 2020 [...] We will fund Housing Zones to transform brownfield sites into new housing, which will create 95,000 new homes.'

'Prioritise development on brownfield and town centre sites and bring to an end the permitted development rights for converting offices to residential.'

We were pleased to see our work on Waste of Space recognised by our peers by being shortlisted for the environment campaign section of the Charity Awards. But there was more to do to make brownfield first a reality.

Thanks to the political momentum from the election, the new government set up a pilot project with a few councils to see what sort of figures they came up with when asked to register brownfield land suitable for housing.

With the new evidence, we set about lobbying ministers, MPs and explaining our work to civil servants. They started showing an interest: the No 10 Policy Unit asked to see what sites were on our crowd-sourced list.

In March the following year we published the policy paper Better brownfield suggesting that large scale brownfield sites require a comprehensive approach to development - and European experience could show us the way. It also looked at small-scale brownfield sites in England, finding that a register of these sites together with a flexible approach to space standards could make the most of their potential.

A commitment to brownfield land appeared in Conservative and Liberal Democrat manifestos for the 2015 elections.

'We will require local authorities to have a register of what is available, and ensure that 90 per cent of suitable brownfield sites have planning permission for housing by 2020 [...] We will fund Housing Zones to transform brownfield sites into new housing, which will create 95,000 new homes.'

'Prioritise development on brownfield and town centre sites and bring to an end the permitted development rights for converting offices to residential.'

We were pleased to see our work on Waste of Space recognised by our peers by being shortlisted for the environment campaign section of the Charity Awards. But there was more to do to make brownfield first a reality.

Thanks to the political momentum from the election, the new government set up a pilot project with a few councils to see what sort of figures they came up with when asked to register brownfield land suitable for housing.

The search for brownfield steps up a gear

In March 2016 we had more good news: CPRE research commissioned from planning consultants, Glenigan, revealed that brownfield sites are on average built out more than six months quicker than greenfield once they have planning permission. Small brownfield sites are particularly important in countryside areas: they are key to increasing the supply of new housing and can play an important role in maintaining the vitality of rural communities.

And in November 2016 we were delighted to find out that when we analysed the pilot projects data, it suggested our researchers’ original calculations were on point: suitable brownfield sites across England could provide at least 1.1 million new homes.

The government had described our estimate of around 1 million homes as ‘wildly over optimistic’. Now, using the government’s own pilot scheme results, we could see the results on the ground. Looking at the data of the 53 councils involved in the pilot project, we found that these areas alone could provide 273,000 homes.

In March 2016 we had more good news: CPRE research commissioned from planning consultants, Glenigan, revealed that brownfield sites are on average built out more than six months quicker than greenfield once they have planning permission. Small brownfield sites are particularly important in countryside areas: they are key to increasing the supply of new housing and can play an important role in maintaining the vitality of rural communities.

And in November 2016 we were delighted to find out that when we analysed the pilot projects data, it suggested our researchers’ original calculations were on point: suitable brownfield sites across England could provide at least 1.1 million new homes.

The government had described our estimate of around 1 million homes as ‘wildly over optimistic’. Now, using the government’s own pilot scheme results, we could see the results on the ground. Looking at the data of the 53 councils involved in the pilot project, we found that these areas alone could provide 273,000 homes.

Going up

Spring 2017 saw the move we’d been pushing for: the government published regulations requiring all planning authorities to publish a register of brownfield land by the end of 2017.

By the end of the year, more than 95% of local planning authorities in England had published their surveys of available brownfield land, and we had the chance to look at the pilot registers. By extrapolating the results, we were reassured to see that they suggested our figure was a lot more realistic than the government’s 200,000.

Our analysis revealed that local planning authorities had identified brownfield land with space for more than 1 million homes, and that, importantly, there was brownfield land in places where people wanted to live.

New report out today: Local planning authorities could be missing small brownfield sites with the potential to deliver nearly 200,000 homes – land that could be used for housing without unnecessary loss of our countryside. https://t.co/8vjU4GPAJP pic.twitter.com/hVywY1jJhO

— CPRE The countryside charity (@CPRE) December 12, 2017

If this land was used more efficiently, the sites could deliver even more homes, closer to 1.4 million – preventing the unnecessary loss of countryside and green spaces.

In early 2018 we finally had the chance to analyse councils’ brownfield registers in full – and guess what? CPRE was right all along.

The published registers showed suitable brownfield sites, as identified by local councils, for more than one million homes. Much of this capacity was ready to start building. It was even feasible for two-thirds of those homes to be delivered over the following five years, representing 60% of official figures for housing need at that time.

The government dismissed us when we said there was enough brownfield land to build more than 1 million homes. Now we've been proved right. Full story here: https://t.co/JnsF07XEu8 pic.twitter.com/eNMaUj8X4z

— CPRE The countryside charity (@CPRE) February 13, 2018

Spring 2017 saw the move we’d been pushing for: the government published regulations requiring all planning authorities to publish a register of brownfield land by the end of the 2017.

By the end of the year, more than 95% of local planning authorities in England had published their surveys of available brownfield land, and we had the chance to look at the pilot registers. By extrapolating the results, we were reassured to see that they suggested our figure was a lot more realistic than the government’s 200,000.

Our analysis revealed that local planning authorities had identified brownfield land with space for more than 1 million homes, and that, importantly, there was brownfield land in places where people wanted to live.

New report out today: Local planning authorities could be missing small brownfield sites with the potential to deliver nearly 200,000 homes – land that could be used for housing without unnecessary loss of our countryside. https://t.co/8vjU4GPAJP pic.twitter.com/hVywY1jJhO

— CPRE The countryside charity (@CPRE) December 12, 2017

If this land is used more efficiently, the sites could deliver even more homes, closer to 1.4 million – preventing the unnecessary loss of countryside and green spaces.

In early 2018 we finally had the chance to analyse councils’ brownfield registers in full – and guess what? CPRE was right all along.

The published registers showed suitable brownfield sites, as identified by local councils, for more than one million homes. Much of this capacity was ready to start building. It was even feasible for two-thirds of those homes to be delivered over the following five years, representing 60% of official figures for housing need at that time.

The government dismissed us when we said there was enough brownfield land to build more than 1 million homes. Now we've been proved right. Full story here: https://t.co/JnsF07XEu8 pic.twitter.com/eNMaUj8X4z

— CPRE The countryside charity (@CPRE) February 13, 2018

Next steps

Since then we've regularly analysed councils' brownfield registers.

Our annual State of Brownfield reports review published brownfield registers from all planning authorities. The analysis continues to show that there's enough suitable brownfield land available in England for more than 1 million homes across over 18,000 sites and over 26,000 hectares. And, satisfyingly, we can see that the suggestion made in 'From Waste of Space' way back in 2014 - that brownfield is a renewable resource - is demonstrably true.

Using suitable brownfield land for housing is one of the best ways to build the homes we need while protecting the countryside.

— CPRE The countryside charity (@CPRE) June 4, 2019

But building on brownfield land is at a five-year low.

Here's why the government should adopt a genuine #brownfieldfirst policy. pic.twitter.com/VQzbM2YSq5

In 2021, Richard Rogers’ introduction to our 2014 report remains as true now as it did then:

‘There is nothing to suggest that our supply of brownfield sites is running low. We should focus on better planning and funding systems to build new towns – but in our towns and cities, not on inaccessible and unsustainable greenfield sites.’

What’s happening now?

CPRE is continuing to monitor the brownfield registers and the rate of building on brownfield land. 2021 saw us publish another 'state of brownfield' report, called 'Recycling our land', which explores how much land is available on local authorities' brownfield registers throughout England.

The report also examines how efficiently this land has been used for development by looking at the density in which it has been built and the number of affordable homes that have been provided.

We're also devising a plan to expand our brownfield beyond just monitoring brownfield land, to identifying it too. We hope to engage volunteers and local communities in helping us find the true potential of brownfield land across the country. Look out for more details to come.

Land Use Officer Philippa Oppenheimer tells us what's next for CPRE's brownfield work

Land Use Officer Philippa Oppenheimer tells us what's next for CPRE's brownfield work

How you can get involved

Our brownfield campaign was built with the help of our supporters who gave their time, voice and donated to support the campaign. See how you can get involved with CPRE The countryside charity.